Neuroscience Could Shape the Future of Public Spaces

California-based, internationally focused nonprofit studies the intersection of neuroscience and architecture to track human responses to the built environment By Alison Whitelaw The last transformative change in architecture began with a simple understanding about the effects building design and construction have on our planet. This symbiosis between archit

Neuroscience Research Promises to Elevate the Human Experience in the Architectural Environment

Neuroscience Research Promises to Elevate the Human Experience in the Architectural Environment

Intersection: Architecture & Neuroscience

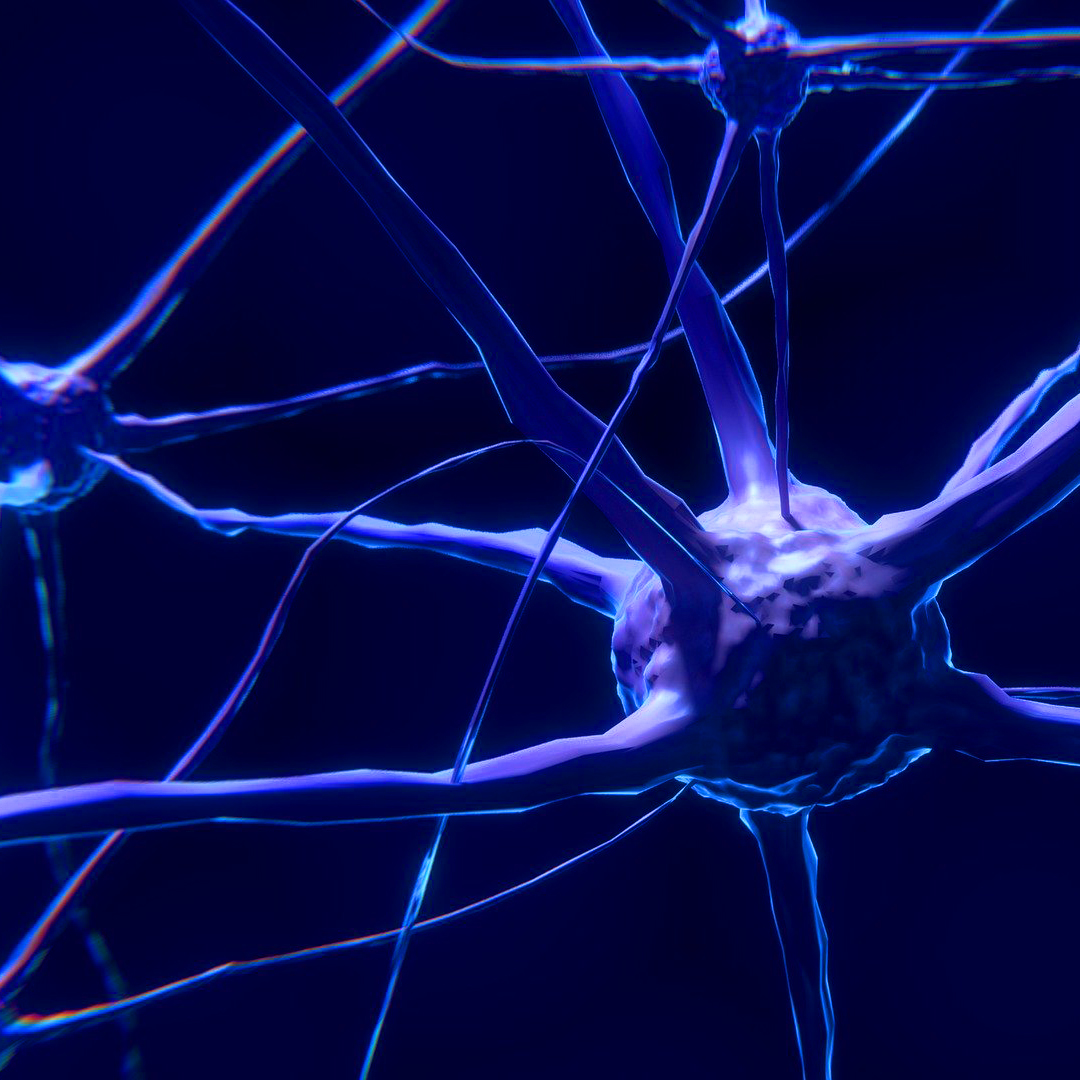

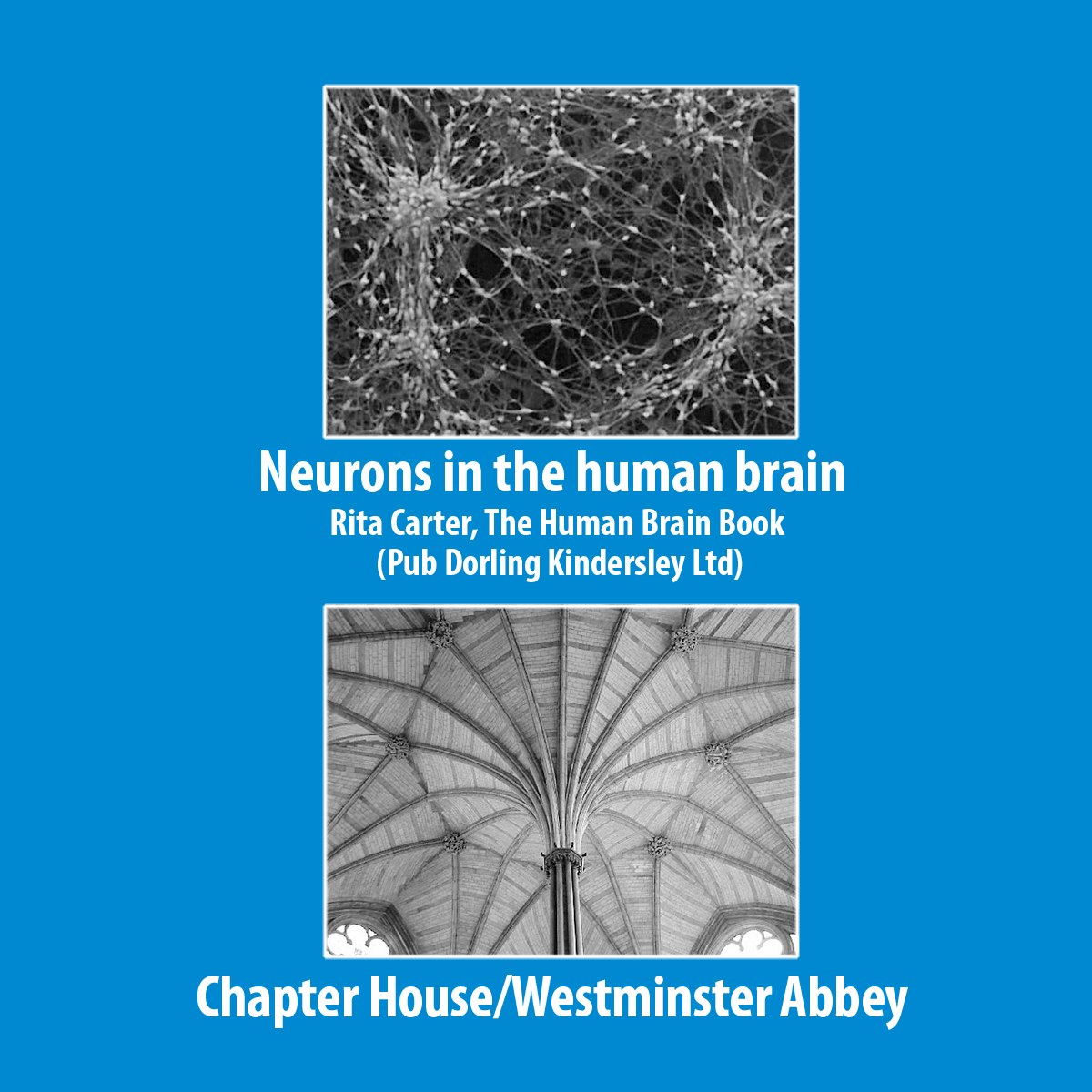

As students, we travel from one class to the next—one for science, one for math, one for art, and so on. Ultimately, though, it’s the integration of this learning that inspires new ideas and new ways of thinking—an integration happening right now between architecture and neuroscience. Every new discovery has ripples, as different professions consider [